The New Aesthetic and Art: Constellations of the Postdigital, Scott Contreras-Koterbay, Łukasz Mirocha, Theory on Demand #20, Amsterdam, Institute of Network Cultures, 2016.

[EN]

[…] With the work of artists who use digital techniques we have an entirely different but related set of issues: are artists utilizing the digital media merely as a means towards an end or is the creative process guided by the software regardless of artists’ intentions? Artists like Mathieu Tremblin, Benjamin Grosser and Aram Bartholl have been creating work that explores the implications not only of the use of digital media but also our ability to control such media.

What needs to be addressed is how New Aesthetic objects or New Aesthetic art objects – and there absolutely is a difference – necessitate new forms of aesthetic evaluation. It can be argued that advocating an increasing awareness of the inescapabilty of digital manifestations opposes the continuation of aesthetics in the traditional sense as it finds itself practically incapable of accounting for an aesthetic system that is self-substantiating;

[…]

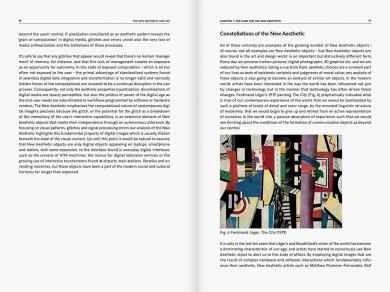

It is only in the last ten years that Légers and Baudrillard’s vision of the world has become a dominating characteristic of our age, and artists have started to consciously use New Aesthetic styles to alert us to this state of affairs. By employing digital images that are the result of complex hardware and software interactions which fundamentally influence their aesthetic. New Aesthetic artists such as Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Ralf Baeker, Mishka Henner, Aram Bartholl, and Mathieu Tremblin remind us not only about New Aesthetic’s limitations and unreliability but its effect that itself limits and makes increasingly unreliable our experience of the world. This is extremely important in the computer-driven age that we live in, in that the world is becoming computer-driven and computer-determined. The authors of New Aesthetic, New Anxieties write that The New Aesthetic, in other words, brings these patterns to the surface, and in doing so articulates a movement towards uncovering the « unseen », the little understood logic of computational society and the anxieties that this introduces. Often, it is artists who best capture the anxiety and the potential in the underlying conditions, and we look forward to discussing ways in which contemporary artists are both utilizing and responding to the New Aesthetic.

[…]

This sense of finding a space between the real and the digital is present in an equally interesting fashion in the work of Mathieu Tremblin, a French street artist. Seemingly borrowing certain artistic strategies from a tradition of artists going back to Kurt Schwitters coupled with an acute sense of the functionality of the urban environment, Tremblin’s work can best be described as urban interventions. Rainwater Popsicles (2014) uses discarded popsicle sticks and collected rainwater in a lyrical fashion to return the pleasure back to the environment; Sourires Volés (Stolen Smiles) (2014) consists of smiles removed from ubiquitous political posters redisplayed in a more congenial fashion; Copying Van Gogh (2013) and Hakim (2015) are re-appropriations of found graffiti tags that simultaneously question and assert the authenticity of street art. For our purposes, however, Tremblin’s most important work is Watermark (2013).

An initial observation sees the image appearing as a watermarked digital photograph, similar in style to that found in the Getty Images library, but further investigations reveals that the watermark is carefully spray-painted onto the wall of the car park. Tremblin has noted that most of his interventions have had an almost curious banal quality to them, as if any ordinary citizen could have arranged the objects involved in a way that wouldn’t be art at all, but Watermark is obviously something different; the image on Tremblin’s website, the appearance of the graffiti in the photograph, all speak to a carefully planned execution that exemplifies what Tremblin refers to as ‘a certain dynamic using photography, graffiti and site-specific installation to end up with this attitude where we’re making forms of art in symbiosis with the context of its creation or diffusion, turning everyday life spaces in experimental art spaces’. Almost every artwork by Tremblin can be understood within the context of this statement, but Watermark is something more; as Tremblin noted, the work came out of his criticism of the city of Mons’ attempt to control its imagery in anticipation of its designation as a ‘European Capital of Culture’ in 2015, which Tremblin saw as being contrary to the representation of the identities of its ordinary citizens. The sense that this is close to the New Aesthetic lies readily in this last point; Tremblin’s work not only highlights the growing usurpation and economic colonization of the public sphere (and literally of public spaces) through increasingly draconian interpretations and applications of copyright and intellectual property laws, in the confusion generated by the seeming dichotomy of its appearance there’s a clear sense that the primary means of such encroachment into the lives of ordinary human beings is not only facilitated by the digital but driven by the digital. Therein lies the even greater impact of Watermark: Plato’s artist, imitating the world and thereby making art simply by holding up a mirror to everything around him or her, doesn’t just imitate the world but ends up owning the images and, thereby, owning the world; the lyrically horrifying effect of Watermark is rooted in a heightened awareness that the digital presence visible here, in an almost ghostly fashion, is a means of taking possession of the world in the same fashion in a way normally unseen but still, as an unseen watermark, very much present in its representation. In effect, everything that can be digitally photographed is now owned by the possibility of those photographs being digitally watermarked by Getty Images.

[…]

Sandbox creates unseen vistas firmly grounded in our understanding of the world which are continually being renewed as otherworldly. Project Blinkenlights took a public space and made it even more public while at the same time transforming participation into an entirely private matter, and Ikeda’s work transforms our understanding of our place in the universe into a sequence of lights and sounds that reduces our ability to differentiate our experiences, our lives and our language into the mathematical and thereby into something immensely depersonalized. Tremblin’s Watermark achieves the same effect, though in a lyrical rather than immersive fashion. It’s when these and other examples of art, immersive and all encompassing, affect us that the categorical conditions of existence of New Aesthetic art are revealed.

Scott Contreras-Koterbay and Łukasz Mirocha, 2016.

Tags: publication, text